|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

Tabla de Contenido/ Table of Contents

- 1 This is how our public assets are negotiated: The case of (affordable housing). The county has handed over our land — in the name of a “public-private partnership”

- 2 The land: a public jewel handed over

- 3 What did we get in return?

- 4 Market comparison: a bad deal?

- 5 Special Report – May 14, 2024

- 6 We demand answers:

This is how our public assets are negotiated: The case of (affordable housing). The county has handed over our land — in the name of a “public-private partnership”

While thousands of residents in Miami-Dade live on the brink of eviction, the county has handed over our land—in the name of a “public-private partnership”—a parcel valued at more than $33.6 million to build a luxury tower in Brickell. The result? Of the 465 apartments built, only 93 are allegedly affordable for low-income people. The rest are available for prices ranging from $2,656 to $4,603 per month, far beyond the reach of the average resident.

The land: a public jewel handed over

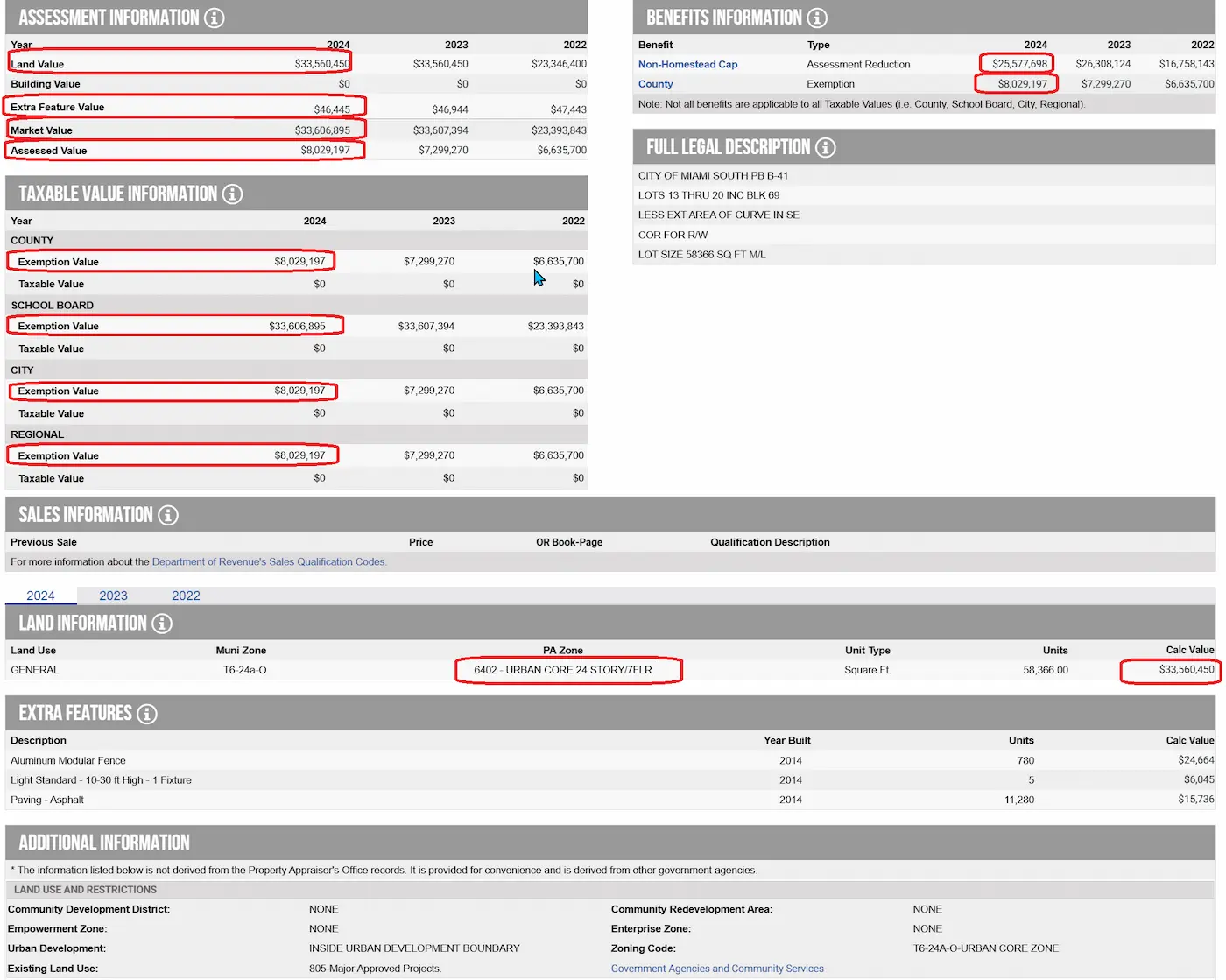

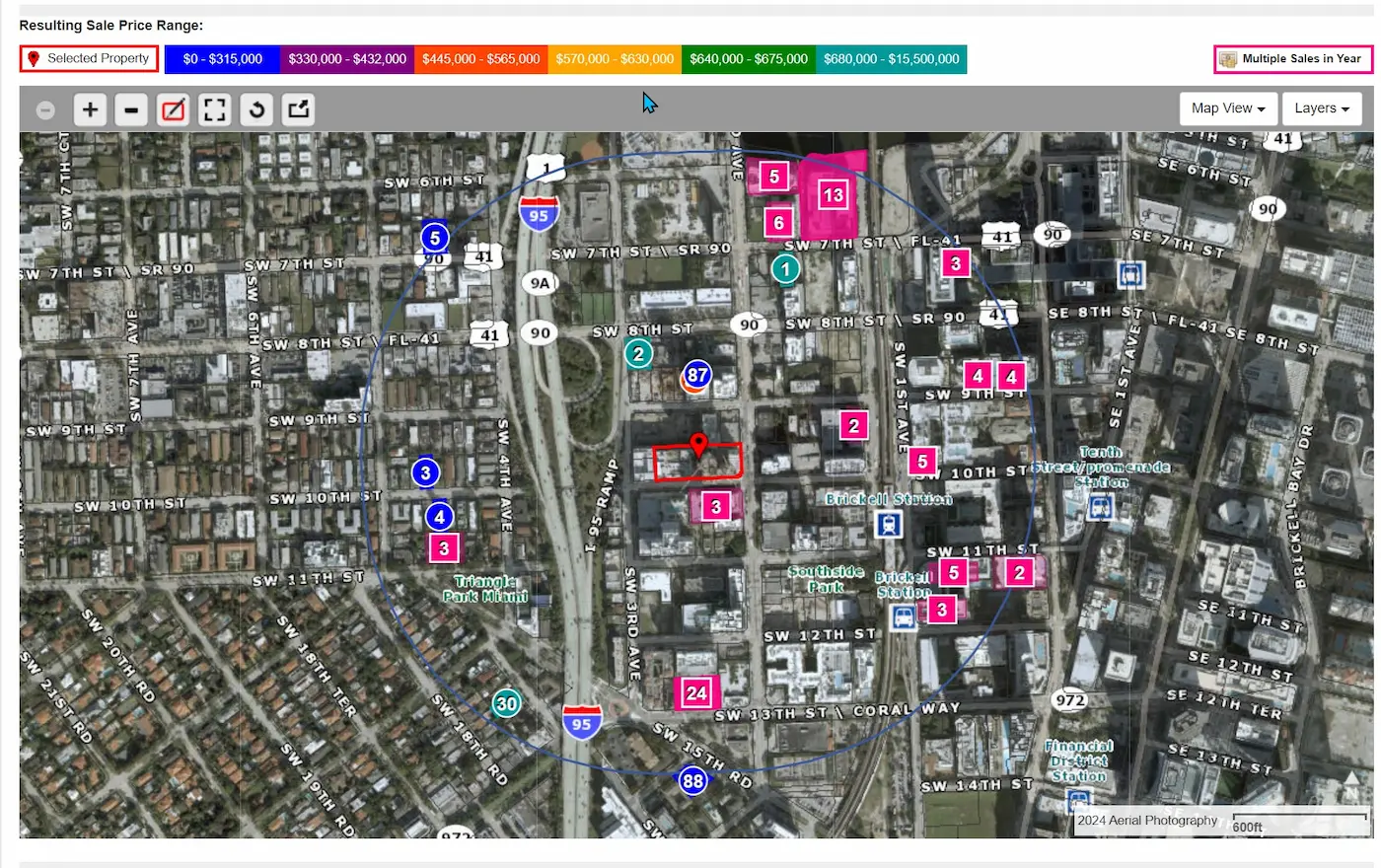

The 29-story Magnus Brickell tower, located at 201 SW 10th Street, was built on a 58,366-square-foot (1.34-acre) lot owned by the county. This land belonged to the Miami-Dade Housing Agency (MDHA) and was previously occupied by a senior housing complex.

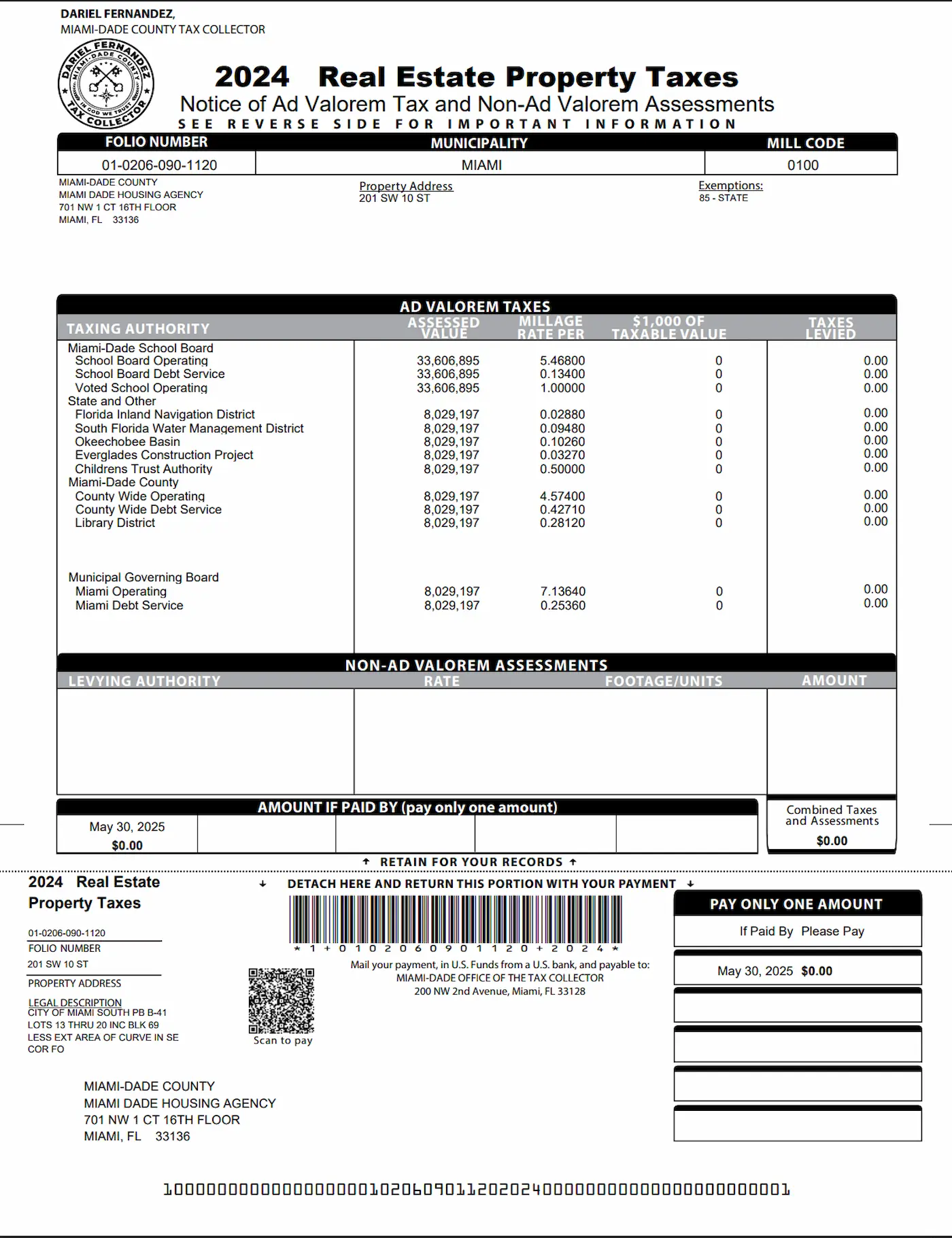

According to Property Appraiser records, the land has an assessed value of $33,606,895 and has been exempt from taxes due to its public ownership. That is, in addition to the land, the county has not collected a single dollar in taxes from this property in recent years.

What did we get in return?

Of the total 465 residential units:

- 93 units are reserved for people earning less than 50% of the area median income. Will the same seniors who lived in the demolished 96 apartments now enjoy the sauna and podcast room?

- 70 units for those earning up to 140% of the average.

- 302 market-rate units, with rents between $2,656 and $4,603 per month.

The breakdown makes it clear that only 20% of the total is allegedly affordable, despite the use of a multimillion-dollar public lot.

Market comparison: a bad deal?

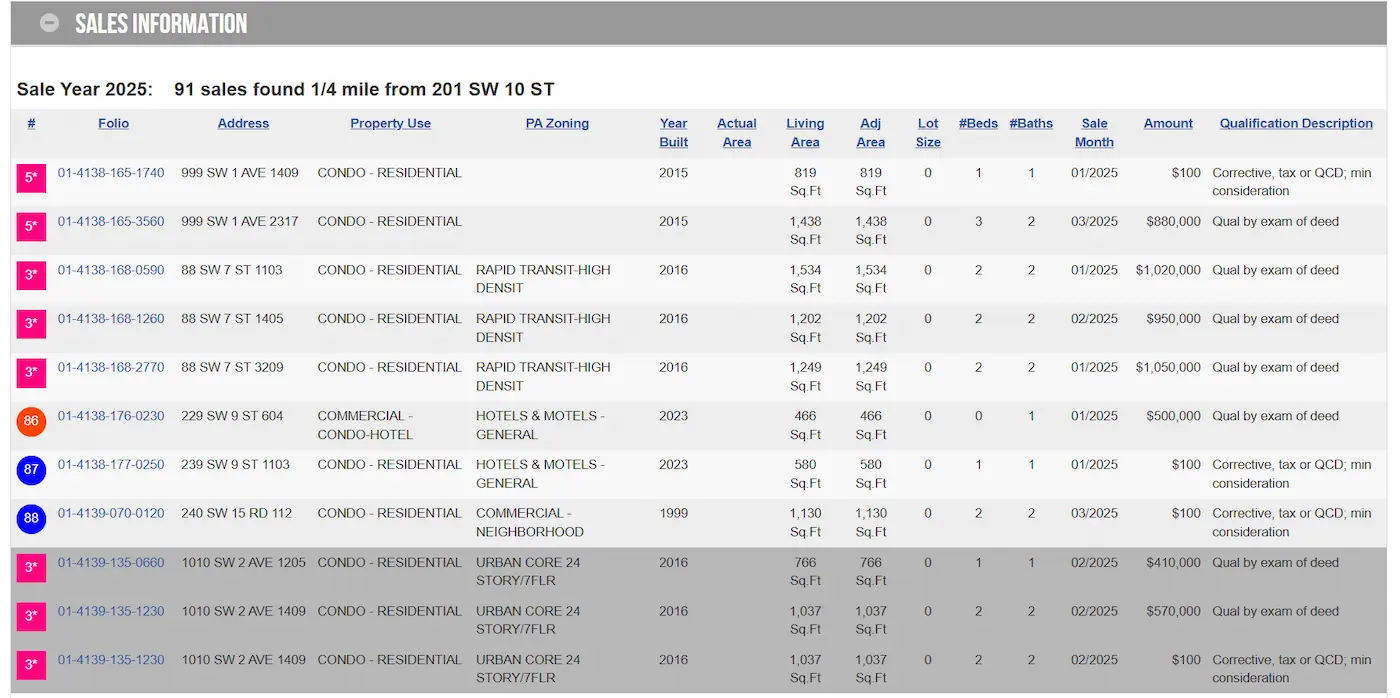

In the same Brickell area:

- A one-bedroom, 800-square-foot apartment has sold this year for between $410,000 and $880,000 (according to Property Appraiser records).

- Each unit could be worth between $450,000 and $950,000.

How many public housing units could have been built with such land?

With land of that value and available federal funds like ARPA, it would have been possible to build more than 200 fully affordable housing units—without subsidizing market-rate units.

TThe “hidden deal” behind projects like Magnus Brickell is not only in what is advertised, but in what is left unsaid. Here are the most evident (and some less obvious) elements that reveal how a private real estate operation is disguised as a social initiative:

Disguising a privileged acquisition as “affordable housing”

- The project is presented as a “solution to the housing crisis,” yet the agreement with the county includes only 20% allegedly affordable units.

- The developer receives a centrally located, publicly owned, tax-exempt parcel without competing in the open market.

Securing county and federal funding without proportional social return

- The county provides the land and possibly infrastructure, exemptions, and public guarantees.

- In return, the developer builds mostly market-rate units renting for over $3,500/month.

Locking in future phases and long-term contracts

- The developer strengthens ties with the county, paving the way for future contracts, concessions, or expansion of other projects (e.g., schools or parking).

- By building on county-owned land, the operator can negotiate favorable management of parking facilities, schools, community centers, or public spaces.

Avoiding open bidding

- As a “public-private partnership,” there’s no open competition or public auction for the land.

- This favors a select group of developers—in this case, the powerful Related Group.

Consolidating political influence and indirect returns

- Developers make legal donations to political campaigns, boosting their standing with officials who approved the project.

- By delivering a small portion as “affordable housing,” politicians claim success in the press, though few actually benefit—and the business is worth millions.

Silently expelling former residents

- The 96 senior housing units were demolished.

- No information has been released on how many original residents returned or were relocated.

- Gentrification disguised as social justice.

Artificially inflating area value using public funds

- The state invests in transportation, schools, and urban spaces.

- This boosts market value… but benefits go to private investors, not historic residents.

Evading real oversight of ARPA and HUD funds

- No clear financial reports are published.

- No one answers how many dollars from these programs truly help low-income individuals.

More than housing: luxury and marketing

Among the project’s “amenities” are:

- Resort-style pool

- Cinema and podcast room

- Luxury gym

- Summer kitchen

- Wellness studio with massage therapy

All this partly financed by the free transfer of public land. Meanwhile, thousands in Liberty City, Allapattah, and Brownsville live in unrecertified buildings, surrounded by septic tanks and without access to decent housing.

And what about the public school?

- The project includes a K-8 school on the same lot, also under construction.

- While it sounds good on paper, it’s still unclear how much the county has invested and whether the school will truly be accessible—or just a “luxury annex” for new residents.

The hidden cost: subsidies, taxes, and privileges

The county not only gave away the land. It also:

- Granted tax exemptions.

- Covered infrastructure costs.

- Participated actively through the Office of Housing and Community Development.

The people provide the land; the developer takes the profit

The Magnus Brickell case mirrors what happens daily in Miami-Dade. Policies claiming to help the needy ultimately benefit developers at the expense of public assets.

Where are the former residents of the senior building? How many returned? How many were promised a place… but no longer fit in the new Brickell?

Proyectos 100% Públicos (PHCD + HUD)

| Proyecto | Unidades | Público objetivo |

|---|---|---|

| Liberty Square | 709 | Familias |

| Robert King High Towers | 315 | Adultos mayores |

| Claude Pepper Tower | 166 | Adultos mayores |

| Haley Sofge Towers | 475 | Mixto |

Proyectos Mixtos (Público + Privado)

| Proyecto | Desarrollador | Unidades totales | % Asequibles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liberty Square Rising | Related Group | 1,200 | 50% |

| Smathers Plaza | Pinnacle Group | 182 | 100% |

| Northpark at Scott-Carver | Atlantic Pacific | 287 | 62% |

| Casa Matias | Carrfour | 150 | 100% |

Key Affordable Housing Projects (2023–2025)

(Mixed Public and Private Funding)

| Project | Location | Total Units | Affordable/Workforce Units | % Reserved | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexandria Gardens | Opa-locka | 225 | 28 | 12.5% | Not using Live Local Act; in Rapid Transit Zone; includes playground |

| Delmas North Apartments | NE 2nd Ct, Miami | 80 | 80 | 100% | $16.5M loan; no amenities to reduce costs |

| Wyn Mood C | Wynwood Norte | 72 | 14 | 20% | Close to public transport; minimalist design |

| The Eden | S. River Dr, Miami | 454 | 56 | 12.5% | Scaled down after official review |

| Laguna Gardens | Miami Gardens | 341 | ~100 | ~30% | Among first Live Local Act projects; garden-style design |

| Sawyer’s Walk | Overtown | 578 (est.) | 578 | 100% | For low-income seniors; full public transit and service access |

| Valencia Tower | Goulds | 159 | 40 | 25% | Includes pool, retail, and parking |

| Horseshoe Cay Apartments | SW 118th Ct, Miami | 44 | 4 | 10% | Small project; community-focused |

| Earlington Heights Towers | NW 41st St, Miami | 856 | ~100 | ~12% | Massive two-tower complex; modern amenities |

| Aventana | Harriet Tubman Hwy, Miami | 344 | 34 | 10% | 16-story tower; premium amenities |

| Casa Matias | Naranja | 80 | 80 | 100% | For homeless and low-income families; includes support services |

| Redwood Mosaic Apartments | Opa-locka | 98 | 98 | 100% | First major Opa-locka project in 10+ years; includes entrepreneur units |

| City Terrace (Phase I) | Opa-locka | 444 | 200 | ~45% | Mixed-use; aims for urban revitalization and job creation |

Main Private Developers Involved in PPP Housing in Miami-Dade

- Related Group – Liberty Square Rising, and others

- Pinnacle Housing Group – Smathers Plaza, Tropical Crossings

- Atlantic Pacific Companies – Northpark at Scott-Carver

- Carrfour Supportive Housing – Casa Matias, Little Havana Mezzanine

Issues Identified

- Limited Affordability: Most projects reserve only 10%–30% of units as affordable, often targeting those earning 60%–120% AMI. Truly low-income families (<50% AMI) benefit the least.

- Resident Displacement: Some developments replace existing housing without clear relocation plans.

- Luxury Over Necessity: Prioritize amenities like pools or gyms over essential services like health access, nearby schools, or job connectivity.

- Lack of Transparency: Public contributions (land, exemptions, infrastructure) often go unreported.

Projects Funded by the Miami Forever Bond

The Miami Forever Bond, approved in 2017 for $400 million, allocated $100 million to affordable housing. Highlighted developments include:

| Project | Area | Investment Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Wynwood Works | Wynwood | $3.5 million |

| Essence Miami | Little Havana | $5 million |

| Platform 3750 | SW Miami | $3.5 million |

| Residences at Dr. King Boulevard | Liberty City | $2M (Bond) + $3.8M (County) |

These projects aim to address the shortage of affordable housing in strategic areas of the county.

Identified Challenges

Limited accessibility: Although labeled as “workforce housing,” many units are inaccessible to those earning less than 80% of the AMI (approximately $60,000 annually).

Resident displacement: Some projects replace existing housing without clear plans for relocation or compensation for current residents.

Focus on luxury amenities: Features like pools and gyms are prioritized over essential needs such as healthcare services, nearby schools, or connections to employment centers.

Limited public participation: Many developments move forward with minimal community consultation, which can lead to resistance and distrust among residents.

Special Report – May 14, 2024

“Affordable Housing Pipeline Brief” – Miami Homes For All

- 101 projects in pre-development

- 13,691 proposed units

- $1.5 billion needed in local subsidies to unlock $3.3B already committed

Without this investment, most projects will be canceled or converted to market-rate housing.

Only 15% of the proposed units would be accessible to people earning ≤30% of the AMI.

“Affordable Housing Pipeline Brief 2024 – Miami-Dade Needs $1.5B to Unlock 13,691 Homes”

Event Context

On May 14, 2024, Miami Homes For All publicly presented its report titled “Affordable Housing Pipeline Analysis,” a technical and strategic document that analyzes 101 affordable housing projects in Miami-Dade that are currently in pre-development but lack secured funding.

Key Findings

- Total number of projects: 101

- Total projected units: 13,691

- Subsidy required to unlock them: $1.5 billion (soft subsidy)

- Currently available funds: $3.3 billion (federal funds, tax credits, private mortgages)

- Total financing required (public + private): $4.8 billion

Without the $1.5B in local or philanthropic subsidies, many projects could be abandoned or converted into market-rate developments.

The rise of mixed-financing housing projects in Miami-Dade represents a significant effort to address the affordable housing crisis. However, challenges persist related to the true accessibility of these units, the displacement of existing communities, and the lack of community participation in the development process. Future policies must focus on inclusive and sustainable solutions that truly benefit the county’s most vulnerable residents.

We demand answers:

- How much did each “affordable” unit really cost?

- What did the county contribute in cash, exemptions, and infrastructure?

- Who decided to give away this land and based on what criteria?

Public land belongs to all. It is not meant for private giveaways.

Miami-Dade deserves transparency. Miami-Dade deserves housing justice.