|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

Tabla de Contenido/ Table of Contents

- 1 The New Miami-Dade: A Paradise for Speculators and a Hell for Tenants and Small Homeowners. Caribbean Dubai, Tropical Dubai?

- 1.1 Expansion of the Urban Development Boundary for Logistics and Tech Development in Homestead

- 1.2 Case 1: Bayshore Park (Coconut Grove): The New Model of Legal Expulsion

- 1.3 The “Game of Attrition”: How They Kick You Out of Your Own Home

- 1.4 Slow Justice, Fast Speculation

- 1.5 Public Heritage, a Gift to the Private

- 1.6 Rezoning and Out-of-Control Projects: Big Developers’ Townhouses in South Miami-Dade

- 1.7 The Most Notable Lennar Expansions in Miami-Dade, Focusing on 2024–2025:

- 1.7.1 🏗️ May 2024 – Major boost with +550 townhomes

- 1.7.2 🌾 September 2024 – Acquisition of 38.5 acres in Goulds

- 1.7.3 ⚙️ June 2025 – Retro West proposal of 106 townhouses

- 1.7.4 🌿 June 2025 – Purchase of 12 acres near a nature reserve

- 1.7.5 ✅ 2024–2025 Outlook: Consolidated Strategy

- 1.7.6 Public Incentives and the Live Local Act

- 1.8 Another Giant: Affordable Housing Projects Driven by Related Group in Miami-Dade

- 1.9 Terra Group

- 1.10 🏗️ Main Affordable Housing Developers in Miami-Dade

- 1.11 📊 Quick Comparison

- 1.12 Caribbean Dubai? Yes, but only for those who can pay the entry fee and buy influence. The rest, further away and poorer every day.

- 1.13 Amended Live Local Act (SB 328 – 2024)

- 1.14 🔍 Key Points of the New Legal Text

- 1.15 🧩 Critical Analysis

- 1.16 Lack of Public Strategy and Deficit: The County Depends on Private Developers Because It Has No Plan of Its Own

- 2 Critical Conclusion: What is Happening Socially

- 3 Market reactions and strategies

- 4 📰 Want more news like this?

The New Miami-Dade: A Paradise for Speculators and a Hell for Tenants and Small Homeowners. Caribbean Dubai, Tropical Dubai?

Expansion of the Urban Development Boundary for Logistics and Tech Development in Homestead

In November 2022, the Miami-Dade Commission approved a controversial expansion of the Urban Development Boundary (UDB) to allow the construction of a logistics and technology center near Homestead. This change implied converting 379 acres of agricultural and natural lands, generating intense controversy among county authorities, developers, environmentalists, and residents. The situation is aggravated by the precedent of Mayor Daniella Levine Cava’s veto, which was later overturned by a majority of the Commission.

Key factors in this case:

- Location and land characteristics:

- Exact location: Near Homestead, Miami-Dade (south of the county).

- Original project size: 793 acres (later reduced to 379 acres).

- Original land category: Agricultural and natural lands, previously protected by the urban boundary since 1983.

- Key actors involved:In favor of the expansion:

- Main developers:

- Rock DevelopmentAligned Real Estate Holdings

- Daniella Levine Cava, Miami-Dade County Mayor.

- Environmental groups, mainly Hold the Line Coalition, led by Lauren Reynolds.

- Urban experts and analysts such as Andrés Sánchez, political consultant.

- Main developers:

- Conflicting interests and arguments:Developers and commissioners in favor argue:

- Estimated creation of 11,500 direct jobs and 6,000 indirect jobs over 6-10 years.

- Reduction of mobility to other county areas, improving local quality of life.

- Environmental compensation by ceding 362 acres to the Environmentally Endangered Lands (EEL) program.

- Cleanup of existing contamination in the area and additional environmental commitments to preserve 600 nearby acres.

- Potential severe environmental damage to aquifers and Biscayne Bay.

- Contradiction with existing policies to improve public transport and mobility.

- Risks from climate change, sea-level rise, and flooding.

- Existence of suitable land available within the urban boundary, making expansion unnecessary.

- Concern about creating a precedent that would open a “Pandora’s box,” incentivizing future urban boundary expansions at the expense of protected natural areas.

- Documentary evidence and key facts:

- Original resolution: Approval document by the Commission and subsequent veto by Mayor Levine Cava.

- Veto reversal: Final vote 8-3 against the Mayor’s veto.

- Environmental and urban reports presented to the Commission before approval.

- Official reports and statements from the developer companies justifying their project.

- Testimonies and statements from the environmentalist group Hold the Line Coalition and urban experts questioning the decision.

- Historical context and similar precedents:

- Original creation of the urban boundary: 1983, precisely to prevent urban expansion into sensitive and agricultural natural areas.

- Relevant precedent: Kendall Parkway project previously rejected due to similar pressure from environmental groups and civil society, marking an important precedent on citizen and environmental resistance to these proposals.

- Potential impacts and identified risks:

- Significant environmental risk due to impact on the Everglades and Biscayne Bay, with possible irreversible consequences for the water supply.

- Increase in vehicle traffic to the area, contrary to public transport expansion policy.

- Risk of future flooding due to land vulnerability, especially in adverse climate scenarios.

Case 1: Bayshore Park (Coconut Grove): The New Model of Legal Expulsion

“The business of eviction: Funds buy, expel, and demolish the Miami of a lifetime.” “Condo Buyout: Who defends the small owner against the giants of development?”

In Miami-Dade, history and roots mean nothing when large funds and developers come into play. The massive purchase of units, economic pressure, and subsequent demolition are turning the city into a business where only the usual winners prosper, and those who built community for decades lose.

Bayshore Park, located in Coconut Grove, is one of the most recent examples of the phenomenon known as bulk-buyout, where large developers massively acquire units in old buildings to later demolish them and build luxury properties. This practice not only alters the urban and social fabric but also generates forced displacement and loss of historical-community heritage.

Key factors in this case:

- Identification of the affected building:

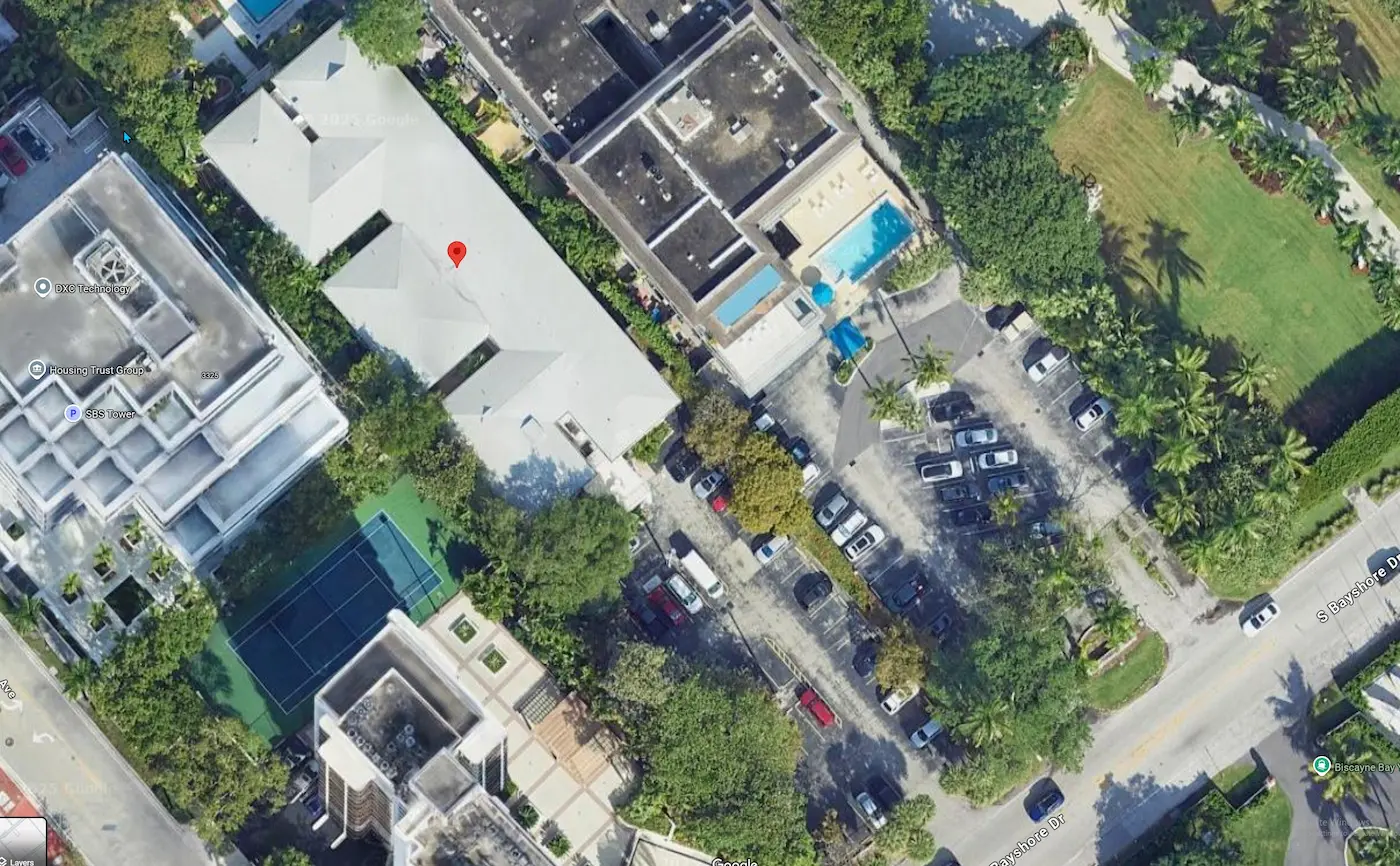

- Name: Bayshore Park Condominium

- Location: 2545 South Bayshore Drive, Coconut Grove, Miami

- Official name: The building is consistently referred to as Bayshore Park Condominium in the sources.

- Year of construction:

- The Real Deal indicates it was completed in 1967

- Other sources like Zillow and Compass estimate completion in 1964, which causes a slight discrepancy compass.com.

- Actors involved:

- Buyer developers:

- Mast Capital, led by Camilo Miguel Jr.

- BH Group, led by Isaac and Liat Toledano.

- Both companies have proven backgrounds in real estate developments and aggressive acquisitions of old properties.

- Financing involved:

- Initial $28 million loan provided by BridgeInvest to facilitate unit acquisition.

- Intermediaries in the purchase:

- Berkadia, represented by Scott Wadler and Mitch Sinberg, actively participated in structuring the project’s financing.

- Buyer developers:

- Applied strategy:

- Gradual and quiet purchase of individual units over several years (since the mid-2010s), initially hiding the buyers’ real identity behind affiliated entities to avoid alerting resident owners.

- Subsequently, a massive acquisition of units (bulk buyout) to obtain the majority control of the condominium.

- Key evidence of the process:

- First acquisition: In the past decade, Mast Capital began buying units for between $240,000 and $450,000, accumulating 16 individually acquired units before the recent bulk buyout.

- Recent bulk purchase: In June 2025, Mast Capital and BH Group acquired over 75% of the condo’s units, an operation estimated at more than $20 million.

- Explicit goal of developers: Demolition and replacement of the current building with a new luxury project.

- Impact for original residents and owners:

- The minority owners who remain face economic and social pressure to sell. Florida law allows majority owners to initiate condo termination, but a minority of just 5% can block this process, creating a complex legal scenario.

- Financial pressure via special assessments may be used as a tool to force the sale of reluctant owners.

- Local context and similar precedents:

- Coconut Grove is currently the object of intense luxury real estate development, driven by large groups like Terra, Related, and Mast Capital. This considerably increases the value of old lands and incentivizes this kind of practice.

- Similar emblematic case: The Perigon Residences in Miami Beach, also developed by Mast Capital, resulted from a similar purchase and demolition of another building (Amethyst Condominium).

Sources:

- The Real Deal: https://therealdeal.com/miami/2025/06/18/mast-capital-bh-complete-bulk-purchase-of-coconut-grove-condos/

- Compass.com https://www.compass.com/building/bayshore-park-miami-fl/756748141322872477

- Bizjournals: https://www.bizjournals.com/southflorida/news/2025/06/27/mast-capital-bh-group-buy-out-bayshore-park-condo.html

Bayshore Park (Coconut Grove) Case:

Mast Capital and BH Group bought more than 75% of the units in an old building (Bayshore Park) and now plan to terminate the association and demolish it to build luxury properties. Those who didn’t sell can be forced out—by law—if only 5% object, but they almost never win.

Real-life translation: the longtime owner is displaced by developers offering quick checks, but far below the value of a new apartment in the same area. Where does that resident go? Real-estate exile, out of downtown, or out of the county.

Strategy:

Funds and companies, often with nominees and opaque partnerships, buy units one by one, “cooking” control of the building behind the backs of the others, until they achieve a sufficient majority to demolish and redevelop. This is happening systematically in Miami Beach, Coconut Grove, Edgewater, North Beach, and any area “desirable” for luxury developments.

The “Game of Attrition”: How They Kick You Out of Your Own Home

“Intentional Attrition: The New Legal Tactic to Evict Residents and Keep Everything.” “Special Assessments: The Trick to Force You to Sell Your Home and Lose”

Sound familiar? Overnight, your building needs “million-dollar repairs” and fees skyrocket. It’s no coincidence: it’s the new legal tactic used by big money to force a sale, evict owners, and seize properties at bargain prices. This is how business is done in today’s Miami-Dade County.

Intentional Attrition:

When a fund or group takes control of the association, investment in maintenance is often reduced, fees are increased, and repairs are postponed. The building deteriorates, conditions become unbearable, and residents (mostly seniors or middle class) feel pressure to sell cheaply.

Increase in “special assessments”:

Following the Surfside case, new legislation mandates reserves and costly repairs. Developers take advantage: when the building can’t afford it, they buy cheap, evict, and demolish.

Slow Justice, Fast Speculation

“If you’re small, you lose: Investors without godfathers are left helpless in Miami’s real estate jungle.” “Judges, funds, and developers: Who protects the common citizen in Miami Beach?”

When ordinary citizens try to demand justice against the maneuvers of developers and funds, the scales always tip toward money and power. In the Three Hundred Collins case, history repeats itself: years of litigation, indifferent judges, and in the end, the small investor loses and the system is exposed.

Those who can, are saved:

“Uninformed” investors or small shareholders (as in the case of Hang Bae Lee in Three Hundred Collins) lose their money; the big players always fall flat, even if everything goes wrong.

Those who can’t, are displaced:

Longtime residents have no legal recourse, no real advocates, and the public administration looks the other way

Public Heritage, a Gift to the Private

The historic Olympia Theater, Miami’s cultural pride, is about to be handed over on a silver platter to private interests under the guise of “rescue” or “education.” What should be a common good, managed with transparency, is becoming a political bargaining chip and a business for a few.

“Miami gives away its history! The Olympia Theater, from cultural jewel to political bargaining chip.” “The Olympia Theater: heritage of all, spoils of a few”

Olympia Theater:

The Miami government is trying to give away (or sell at a bargain price and without bidding) the historic Olympia Theater to a foundation linked to Pitbull for a charter school project, ignoring its heritage value and the potential for public or cultural use.

Who benefits? The group with the best political connections, not the common interest or the community.

Rezoning and Out-of-Control Projects: Big Developers’ Townhouses in South Miami-Dade

“Developers in South Miami-Dade: more townhouses, less community.”.”Unrestrained urbanism: developers bulldoze, residents lose.”

While thousands of families fight to maintain quality of life in their neighborhoods, major developers keep planting townhouses without restraint in the south of the county. The result: more traffic, fewer services, and a more fragmented community, where the only priority is quick profit.

- Developers are launching thousands of homes in the south of the county, taking advantage of cheaper land, often with just a handful of “affordable” units and the rest at market prices. Pressure on infrastructure, schools, and services is ignored.

- The outcome: uncontrolled density, traffic, congestion, and, again, displacement of historic residents who can’t compete.

The Most Notable Lennar Expansions in Miami-Dade, Focusing on 2024–2025:

🏗️ May 2024 – Major boost with +550 townhomes

- Flagship project: Lennar bought land and is building 563 townhomes in South Miami Dade, with a permit granted in early 2023.

bizjournals.com - This is part of its strategy to dominate the single-family and townhouse market in the south of the county, where land is more available and cheaper.

🌾 September 2024 – Acquisition of 38.5 acres in Goulds

- Lennar acquired 38.5 acres in the Goulds area (39 acres) for $16.6 million, intending to build about 100 single-family homes.

bizjournals.com - Confirms its presence in the residential development of the far south of the county.

⚙️ June 2025 – Retro West proposal of 106 townhouses

- Proposal submitted for 106 townhouses in the “Retro West” project in Homestead, a mid-sized development with 244 parking spaces and no major amenities.

bizjournals.com - Reaffirms its focus on densifying communities in South Miami Dade.

🌿 June 2025 – Purchase of 12 acres near a nature reserve

- An affiliate bought 12.34 acres bordering a reserve (Florida City) for $12.34 million, with permission to build townhouses.

twitter.com - Represents an expansion into protected edge areas, leveraging opportunities for residential development integrated with the natural environment.

✅ 2024–2025 Outlook: Consolidated Strategy

| Year | Move | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 | +550 townhomes | Southern area, master-planned market |

| 2024 | 38.5 acres in Goulds | ~100 single-family homes |

| 2025 | Retro West | 106 townhouses in Homestead |

| 2025 | 12 natural acres | Townhouses integrated with the environment |

Lennar maintains a clear strategy: capture large tracts of land in the south of the county, where it’s more affordable, focusing on projects ranging between 100 and 600+ units. This allows them to dominate key segments of the residential market, especially in growing communities like Goulds, Homestead, and areas near nature reserves.

Public Incentives and the Live Local Act

- Lennar has explored applying under the Live Local Act, which allows skipping zoning codes if part of the project includes affordable housing.

- This law has been criticized for allowing “simulated affordability,” that is, only a minimal portion of the project must meet requirements to obtain huge zoning benefits.

Another Giant: Affordable Housing Projects Driven by Related Group in Miami-Dade

🏢 General profile of Related Group

- Founder and CEO: Jorge M. Pérez

- Specialization: Luxury developments, affordable housing, and mixed urban projects with a strong focus on community integration and public-private collaboration.

🔑 Recent key projects (2024–2025)

Major purchases and redevelopments

- Sunny Isles Beach: Purchase of oceanfront condo for $130 million along with Dezer and BH Group (July 2025).

- Dadeland North Metrorail: Acquisition for $20 million for a project of 650 apartments and commercial spaces strategically located next to the Metrorail station (July 2025).

- West Palm Beach: Purchase of old condo for $38 million to build a mixed skyscraper with 40% of units for affordable workforce housing (June 2025).

Luxury towers in strategic areas

- North Bay Village: Proposal of two waterfront towers of 43 floors, in partnership with Macklowe Properties (June 2025).

- Bird Road (near Douglas Road Metrorail): Project of two residential towers together with 13th Floor and LeFrak (May 2025).

- Viceroy Residences in Aventura: Launch of sales for luxury condos, first major recent residential construction in Aventura with BH Group (January 2025).

Affordable housing projects (Related Urban Development Group)

- Magnus Brickell: 29-story building with 465 affordable apartments, in partnership with Miami-Dade Public Schools (May 2025).

- SoMi Parc in South Miami: Second phase approved under the Live Local Act, mixed affordable project (June 2025).

- Miami River Project: 19-story tower, 236 affordable apartments, in negotiation with Miami-Dade County (March 2025).

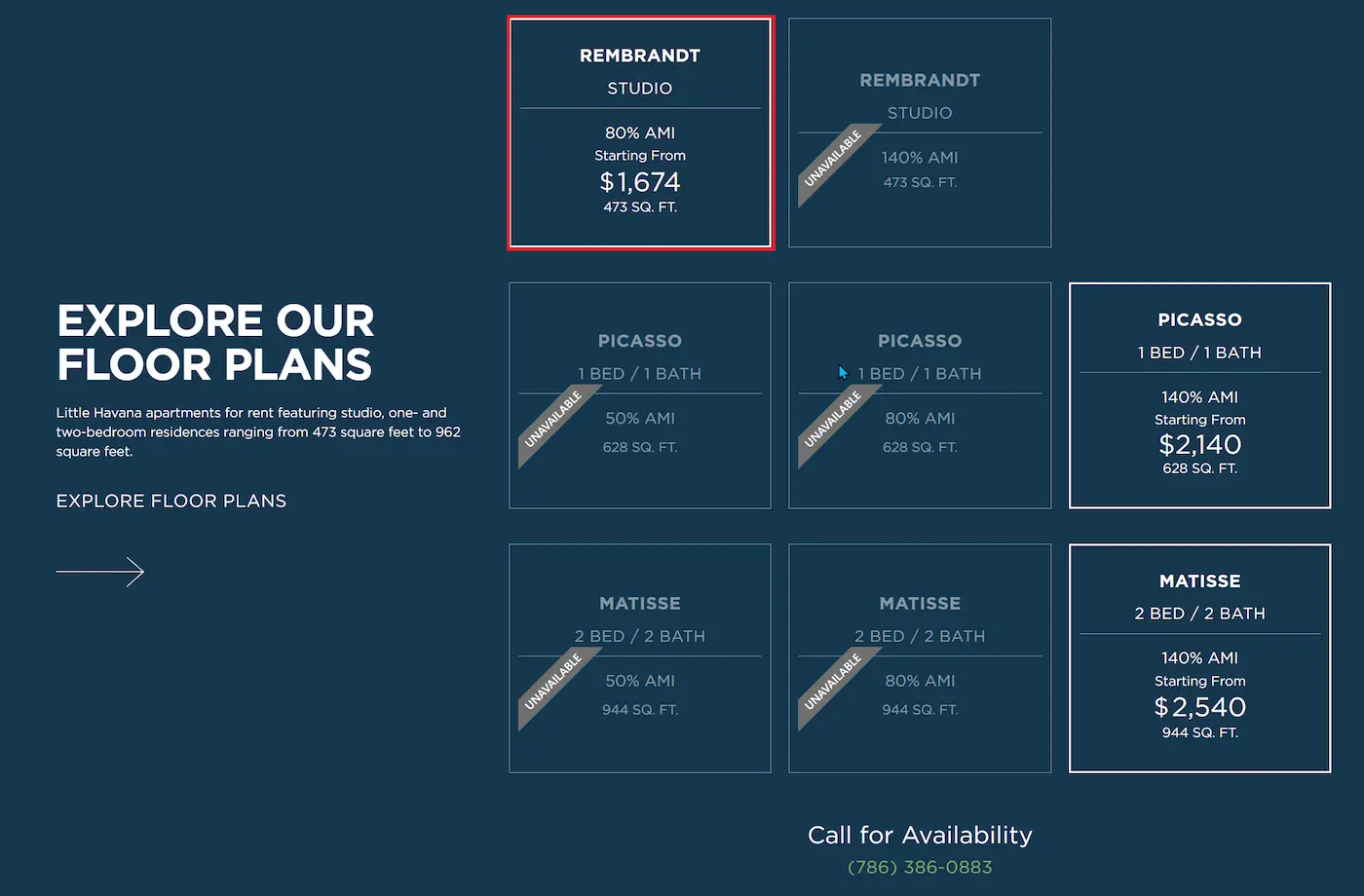

- Little Havana: Expansion with 1,038 affordable apartments in Haley Sofge Towers (January 2025).

- Claude Pepper Tower: Redevelopment in the Miami health district with 398 affordable apartments (March 2025).

- West Coconut Grove: Mixed affordable housing project for $148 million, in alliance with Miami-Dade County (February 2025).

- Hero Housing Tower (Aventura)

- Location: 2999 N.E. 191st St., Aventura

- Description: 26-story residential tower aimed especially at teachers, police officers, and municipal employees.

- Conditions: If they leave their job, they must move or pay market-rate rent.

- Residences at Palm Court (West Little River)

- Location: 860-950 N.W. 95th St., Miami-Dade

- Description: Reconstruction of a public housing complex under a 99-year lease agreement with Miami-Dade County. Project under the Live Local Act to increase density and affordable units.

- River Parc (Little Havana)

- Location: Little Havana

- Cost: $600 million

- Description: Multi-phase project, public-private partnership with Miami-Dade, focused on income mix and affordable housing near public transit.

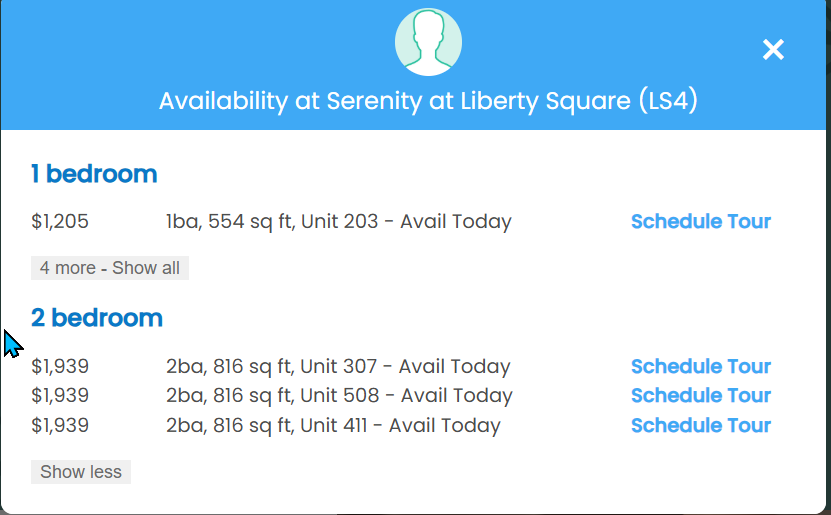

- Liberty Square (Liberty City)

- Location: Liberty City

- Description: Large-scale urban renewal project, more than 1,500 mixed-income units in phases, partnership with Miami-Dade and HUD.

- Gallery at Marti Park (Downtown Miami)

- Location: 450 SW 5th St.

- Units: 176

- Model: 75-year lease with Miami-Dade for affordable housing.

- 5215 Flagler Street LLC (Miami)

- Location: Flagler Street, Miami

- Financing: $3.9 million (Miami Forever Bond) for affordable housing near major roads.

- Lincoln Gardens (Miami-Dade)

- Description: Affordable housing project focused on renovating old housing units in urban county areas.

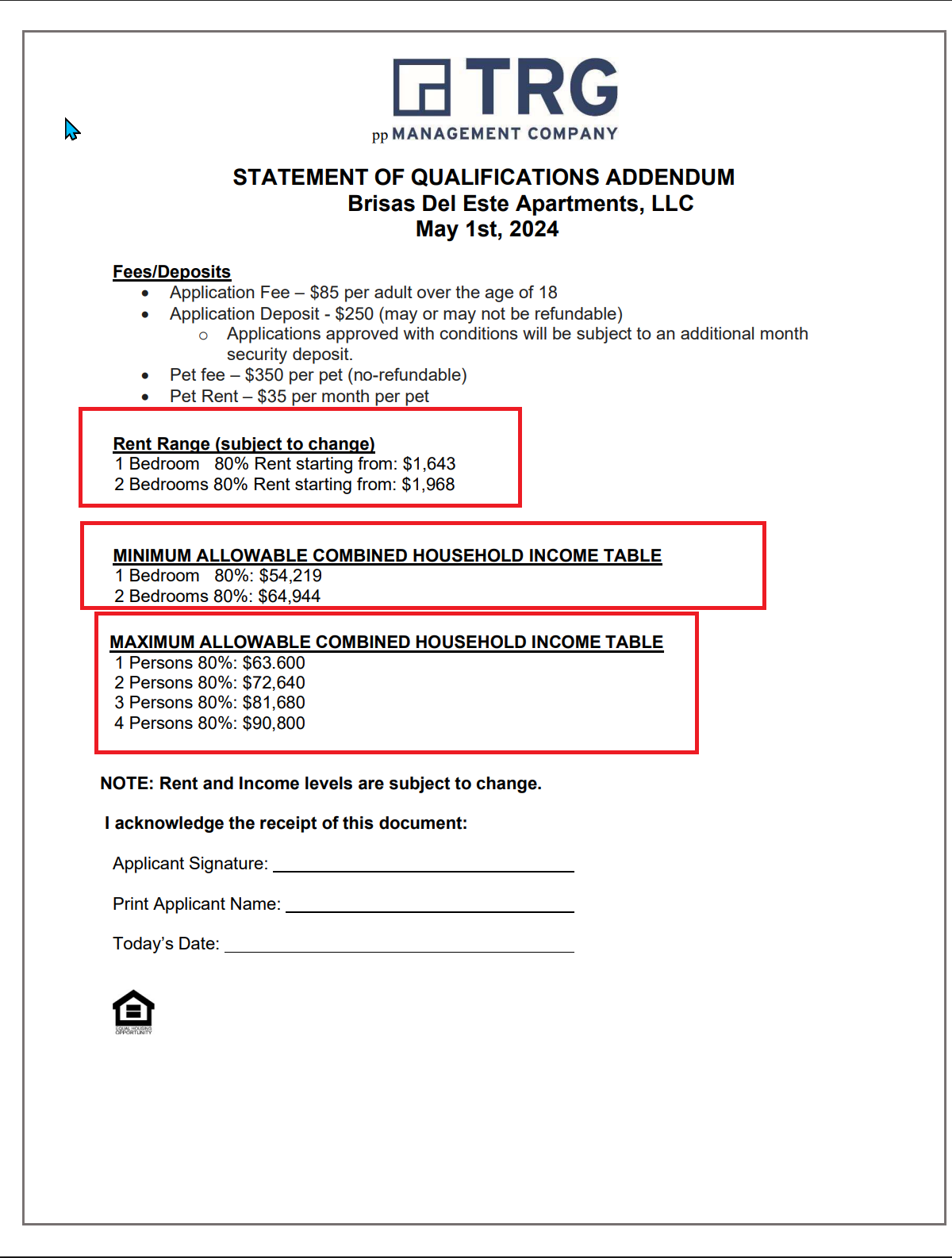

- Brisas del Este (Allapattah)

- Location: Allapattah

- Cost: $106 million

- Details: Construction of 120 new affordable units, renovation of 263 existing ones, and creation of parking. Public-private partnership with the county.

- Smathers Plaza (Miami)

- Description: Construction and renovation of affordable housing through partnership with Miami-Dade Public Housing.

- Paseo del Rio (Miami River)

- Location: 1401 N.W. 7th St.

- Model: Mixed and affordable project on county-leased land.

- Residences at SoMi Parc (South Miami)

- Location: South Miami

- Description: Public-private partnership with Miami-Dade, aimed at mixed-income residential units.

- Gallery at West Brickell (West Brickell)

- Description: Partnership with Miami-Dade County Public Schools to combine affordable housing and a public school.

- Three Round Towers (Allapattah)

- Description: Renovation of 263 existing units in combination with Brisas del Este.

- Brisas del Rio

- Location: Miami (various locations in the county)

- Cost: $20 million loan for affordable housing in partnership with Miami-Dade.

- Hero Housing Project (Aventura)

- Location: Aventura

- Model: Housing reserved for essential municipal employees.

- Affordable housing (Miami River)

- Description: Mixed and affordable housing project along the Miami River on land leased from the county.

- Affordable/Workforce Tower (Miami-Dade public site)

- Location: Miami-Dade County public housing site

- Model: Combination of affordable and workforce housing to renovate aging public sites.

- Park Towers (Miami)

- Description: Purchase and renovation with county loan ($31.5 million) of an apartment complex to maintain affordability.

- Gallery at Lummus Parc (Miami River, Miami-Dade County)

- General description:

- It is a development of two towers of 27 and 30 floors, connected by a skybridge, with approximately 398–440 mixed units (affordable, workforce, and market)

floridayimby.com - Offers from studios to three-bedroom apartments (495–1,220 ft²), along with 478 parking spaces and 5,400 ft² of commercial spaces

skyscraperpage.com - Income composition:

- 20% of the units are for people with incomes ≤ 50% of the AMI, another 20% for workers ≤ 140% of the AMI; the remaining 60% is market-rate

skyscraperpage.com

- 20% of the units are for people with incomes ≤ 50% of the AMI, another 20% for workers ≤ 140% of the AMI; the remaining 60% is market-rate

- Financing and public-private partnership:

- Estimated total project: ≈ $151.7 M

miamicondoinvestments.com - Financing includes low income housing tax credit, HUD funds, municipal loans, QOZ equity (≈ $6 M), and more—with a total cost of ≈ $177 M according to Miami Dade PHCD in June 2024

miamidade.gov

- Estimated total project: ≈ $151.7 M

- Current status (June 2024):

- A request for release of funds was submitted to HUD by Miami Dade PHCD—a major step to unlock federal funds and move towards construction

miamidade.gov

- A request for release of funds was submitted to HUD by Miami Dade PHCD—a major step to unlock federal funds and move towards construction

- It is a development of two towers of 27 and 30 floors, connected by a skybridge, with approximately 398–440 mixed units (affordable, workforce, and market)

- General description:

- Joe Moretti Phase Two

- Location: Little Havana, Miami

relatedgroup.com - Description: Made up of 12 contiguous Art Deco garden-style buildings (each with 8 units), totaling 95 apartments—all 1-bedroom/1-bath—mainly for low-income elderly immigrants on just over two acres.

relatedgroup.com - Dual preservation: Restoration of historic facades and maintenance of the public function of the complex. Supported by the State Office and the City Historic Preservation Office.

- Architectural details: Conservation of original tri-colored terrazzo floors in all units, maintaining historic integrity and modern functionality.

relatedgroup.com

- Location: Little Havana, Miami

📊 Summary Table of Key Affordable Housing Projects (Miami-Dade):

| Project | Location | Units/Approx. | Financial Strategy | Key Partners | Investment/Loan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberty Square | Liberty City | 1,500+ | Public-private, HUD | Miami-Dade County, HUD | – |

| River Parc | Little Havana | Multiphase | Public-private | Miami-Dade County | $600 million |

| Brisas del Este | Allapattah | 383 | Public-private | Miami-Dade County | $106 million |

| Palm Court | West Little River | Increase | Public-private | Miami-Dade County | – |

| Hero Housing | Aventura | Tower (26 floors) | Municipality partnership | BH Group | – |

| Gallery at Marti Park | Downtown Miami | 176 | County lease | Miami-Dade County | – |

| Smathers Plaza | Miami | To be defined | Public-private | Miami-Dade County | – |

| Lincoln Gardens | Miami-Dade | To be defined | Public-private | Miami-Dade County | – |

| Gallery at West Brickell | West Brickell | Mixed | Educational partnership | Miami-Dade Public Schools | – |

| Paseo del Rio | Miami River | Mixed | County lease | Miami-Dade County | – |

| Residences at SoMi Parc | South Miami | To be defined | Public-private | Miami-Dade County | – |

| Brisas del Rio | Miami | To be defined | Public-private | Miami-Dade County | $20 million |

| Affordable/Workforce Tower | Miami-Dade | Tower | Public-private | Miami-Dade County | – |

| Park Towers | Miami | Renovation | Public-private | Miami-Dade County | $31.5 million |

📌 Related Group’s Strategy in Miami-Dade:

- Related Group aims to be the absolute leader in affordable housing production in Miami-Dade.

- Heavily leverages public resources (leases, subsidies, municipal financing).

- Uses state laws and county agreements to maximize density and affordability.

- Strategic combination of comprehensive urban renewal, new construction, and preservation.

- Notable impact in historically marginalized neighborhoods: Liberty City, Allapattah, Little Havana, West Little River.

- Focus on strategic areas:

- Development near public transit stations to maximize connectivity (Metrorail, Douglas Road, Miami River).

- Coastal and consolidated urban areas (Sunny Isles, North Bay Village, Aventura).

- Smart combination of luxury and affordable housing:

- Luxury projects to maximize profitability (waterfront towers).

- Strategic use of the Live Local Act to develop integrated affordable units in the city, ensuring public support and state funding.

- Public-private collaborations:

- Partnerships with Miami-Dade County Public Schools, Miami-Dade County Housing & Community Development, and Jackson Health System to secure public funding and foster social development (Magnus Brickell, Miami River Project, Jackson Health System $1B development).

Terra Group

- Current focus: Market housing, mixed-use, and transit-oriented projects.

- Major developments:

- Centro City: 38 acres with 470 apartments and 350,000 ft² of retail, secured with $291 M in financing (Phase 1 completed March 2025)

multihousingnews.com - Upland Park: $1 B development next to Dolphin Park & Ride hub, 47 acres, 2,000+ units, 282,000 ft² retail, 414,000 ft² commercial

multihousingnews - Various complexes: Grove Central, Natura Gardens, Pines Garden, and 724 affordable units in Cutler Bay under Live Local

terragroup.com

- Centro City: 38 acres with 470 apartments and 350,000 ft² of retail, secured with $291 M in financing (Phase 1 completed March 2025)

- Advantage: Specializes in TOD (transit-oriented development), leveraging proximity to stations and generating large-scale projects with public partners like Miami-Dade.

🏗️ Main Affordable Housing Developers in Miami-Dade

Related Urban Development Group (division of Related Group)

- Specializes in public-private mixed projects combining affordable, workforce, and market units.

- Has managed multiple projects with county and city funding; leverages public land for economic viability.

bizjournals.com

Bluenest Development

- Local builder focused on affordable single-family homes and duplexes ($400k+).

- Operates in emerging areas of south Miami-Dade, managing construction in-house.

- Over 2,500 homes in the pipeline, including Liberty City and Allapattah.

communitynewspapers.com

Pinnacle Housing

- Developer and builder experienced in vertical workforce communities.

- Has presented comprehensive projects under the Live Local Act, although facing cost and financing challenges.

bizjournals.com

Housing Trust Group (and partnerships with Alonzo Mourning) / Rainbow Village

- NGO that has driven projects such as Tucker Tower and Rainbow Village for low-income and elderly populations.

- Focuses on affordable housing with services and convenient locations.

axios.com

Carrfour Supportive Housing

- Leading nonprofit supportive housing organization in the county.

- Has developed over 1,700 units and invested $300+ million in projects for homeless or vulnerable people.

axios.com

SG Holdings

- Commercial development firm with a recent focus on mass affordable housing.

- Plans a $3 B mixed district with thousands of affordable units in Little River/Little Haiti.

costar.com

📊 Quick Comparison

| Developer | Type | Focus | Highlight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Related Urban | Corporate division | Public-private mixed | Known for projects on public land |

| Bluenest | Local company | Affordable single-family | Direct management of costs and construction |

| Pinnacle Housing | Local private | Vertical complexes | Applies Live Local Act under pressure |

| Housing Trust Group / Mourning | NGO/philanthropic | Seniors, families | Rainbow Village, Tucker Tower |

| Carrfour | NGO | Supportive housing | 20 communities, 10k+ people served |

| SG Holdings | Private | Large-scale mixed projects | Little River initiative with community benefits |

Miami-Dade has a diverse ecosystem of actors driving affordable housing from various angles: corporate, local, nonprofit, and community. However:

- Developers need a lot of public help (land, subsidies, flexible rules) to make projects viable.

- The challenge is financial: high construction and land costs work against accessibility.

- The Live Local Act is slowly implemented due to barriers like taxes, financing, and permits.

- The sector needs real public-private collaboration, including models like land trusts (e.g. CLT pilot) and preservation of existing communities.

Overall, there is a capacity infrastructure, but without a comprehensive county strategy or sustained funding (beyond occasional incentives), these isolated efforts do not close the critical gap of more than 90,000 affordable homes.

axios.com

What we are seeing in Miami-Dade is not orderly development or sustainable growth. It’s a feast for funds, developers, “charities” in disguise, and friendly politicians, while traditional owners and lifelong tenants lose their right to the city.

Caribbean Dubai? Yes, but only for those who can pay the entry fee and buy influence. The rest, further away and poorer every day.

Amended Live Local Act (SB 328 – 2024)

The Amended Live Local Act is an expansion and correction of the original Live Local Act passed in 2023. It was designed to incentivize the development of affordable housing through:

- Additional density

- Tax incentives

- Administrative processing (no public hearings)

🔍 Key Points of the New Legal Text

1. Double Tax Incentives

- Tax exemptions are doubled if the project includes at least 71 affordable or workforce housing units.

- Tax exemptions now include proportion over common areas and land, not just units.

💰 For example: if a building has 70% LLA units, 70% of the land and common area value also receives the exemption.

2. Benefits for Projects in Mass Transit Areas

- 20% reduction in parking requirements if half a mile from a train/bus station.

- 0% parking required if in an area designated as “transit-oriented development.”

3. Control in Single-Family Neighborhoods

- Prevents projects in single-family areas with at least 25 contiguous homes from exceeding 150% of the height of the tallest adjacent building or 3 stories (whichever is less).

- Thus, the scale of residential neighborhoods is protected.

4. Prohibitions and Restrictions

- LLA benefits are not allowed in:

- Airport noise zones

- Flight corridors

5. Administrative Clarity

- All benefits (density, height bonuses, etc.) must be approved administratively, without public hearing.

6. Conditions for Existing Projects

- Properties built or renovated in the last five years qualify for tax benefits if units are allocated to the LLA.

🧩 Critical Analysis

✅ Positives:

- Streamlines bureaucratic procedures for developers.

- Makes it financially viable to lower rental costs (estimated: up to $300 per unit).

- Incentivizes the use of land near public transit.

⚠️ Risks and Criticisms:

- Displaces local government (like Miami-Dade) from control over its urban planning.

- Eliminates citizen participation by removing public hearings.

- Can provoke indirect gentrification, disguised as “workforce housing.”

- Favors large developers capable of building at scale, leaving out public or community initiatives.

🏗️ Context for Miami-Dade

Attorney Anthony De Yurre indicated that after the approval of this law, multiple LLA project proposals are expected in the county, especially in areas like Goulds, Little Havana, and near Metrorail stations.

Miami-Dade is currently in a budget deficit, with no clear public affordable housing strategy, and is overly dependent on the private sector. This law further consolidates that dependency, and takes away the county’s autonomy to regulate urban growth and protect vulnerable communities.

The Amended Live Local Act:

- Makes it easier for large builders (like Related Group, Lennar, Shoma, etc.).

- Reduces the county’s ability to implement its own comprehensive public housing plan.

- It is a state response to a real crisis, but without local control, it could result in abuse and speculation disguised as “affordable housing.”

Lack of Public Strategy and Deficit: The County Depends on Private Developers Because It Has No Plan of Its Own

One of the most alarming factors behind the proliferation of partnerships between the public sector and private developers in Miami-Dade is the total absence of a public construction and management strategy for affordable housing. Instead of taking an active role as a developer, owner, and manager of its own housing inventory for working families, the county limits itself to handing over land, subsidies, or bonds to developers, who then operate on their own terms and profitability criteria.

Using developers could be useful if the county maintained ownership of the projects, but that does not happen. Here, taxpayers finance, but benefits and control end up in private hands. The result? Less transparency, less public control, and more gentrification.

This dependence is largely due to chronic financial mismanagement. Under the current administration, Miami-Dade has squandered funds on unnecessary megaprojects (like the Signature Bridge or millions destined for sporting events), while neglecting its obligation to public housing. Now, with a stricter federal government in the post-Biden era, you can no longer just “ask for more money.” Fiscal rules have tightened, and the county budget deficit is estimated at nearly $400 million, according to internal sources.

The county has neither the funds nor the vision. And the housing crisis continues to deepen.

Critical Conclusion: What is Happening Socially

Miami-Dade is experiencing a silent expulsion of its working class. The lack of affordable housing is not just a housing crisis: it is a structural, demographic, and moral crisis.

Despite laws, speeches, and public-private alliances, the root problem is not being solved. Developers still find it more profitable to build luxury housing, banks do not trust tax promises, and the county has neither a clear strategy nor constructive autonomy. They delegate everything to the private sector, and as expected, it builds what is most profitable.

Meanwhile:

- Young people are leaving.

- Essential workers are displaced.

- Historic communities are transformed into empty Airbnb showcases or unattainable condos.

In other words, the city becomes unlivable for those who keep it running.

The lack of workforce housing in South Florida has reached critical levels. The exorbitant costs of land, construction, and financing have incentivized the development of luxury projects, leaving out more than 90% of households earning less than $100,000 a year.

Social impact in residents:

- Migration of young professionals (ages 25 to 34) out of the county.

- Breakdown of the essential workforce: police, nurses, firefighters, and teachers cannot live where they work.

- Socioeconomic polarization and systematic displacement.

Limitations of the Live Local Act (LLA)

Although it was created with good intentions, the LLA has yet to result in any units built under its new rules. Reasons include:

- Construction costs remain unmanageable.

- Scarce financing: banks do not yet recognize the value of tax exemptions.

- Administrative obstacles: delays in permits for water, sewer, and public services.

- Lack of large and affordable plots for garden-style projects (more accessible).

Social impact LLA:

- Frustration among developers who do want to build for the working class.

- Lack of visible results two years after the law was passed.

- Territorial inequality: the neediest sectors (like Little Havana) are left out due to poorly calibrated income criteria.

Market reactions and strategies

Companies have sought alternatives:

- Moving towards less urbanized areas like south Miami-Dade has been the strategy, but with a serious mistake: attempting to develop projects on agricultural lands or ecological reserves, where the zoning code expressly prohibits it. This practice is not only illegal but threatens environmental balance and responsible land use.

- Partnering with churches, cities, or the county to use public or religious land.

- Giving up amenities to lower costs.

- Creating repeatable standard models (Bluenest) or mixed projects (Related) so that affordable units are “camouflaged” among market-rate units.

Social impact:

- Forced urbanization in areas without infrastructure.

- Risk of “modern ghettos” or disguised gentrification.

- Lack of urban cohesion: workers live further and further from their jobs.

Mismatch Between Public Policy and Reality

Although incentives are announced, the system’s design is unrealistic:

- Tax discounts are not enough to offset costs.

- The Live Local Act depends on “private initiative” and there is no strategic public leadership.

- There is no unified policy from the county to build and own its own affordable complexes.

📰 Want more news like this?

Visit our main page to stay up to date with the latest in South Florida and more:

👉 newsmiamidade.com/

Here, information knows no borders, truth with no filters:

Your newspaper in the digital age.